Ron Johnson was right about JCPenney

The latest painful chapter in the JCPenney saga has now been written.

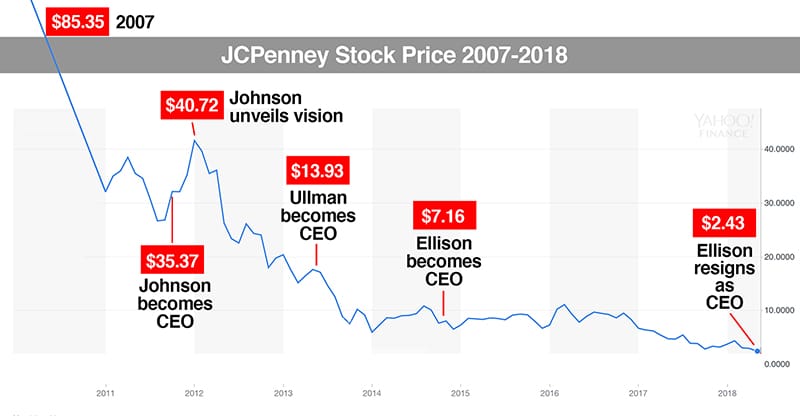

CEO Marvin Ellison resigned a couple of weeks back—with the company’s stock price down to a mere $2.43. That’s a particularly brutal number, considering that in 2007 a share of JCP went for $85.

Technically, this plummet was co-authored by three CEOs serving four terms—Marvin Ellison, Ron Johnson and two stints by Myron Ullman.

By numbers alone, it’s hard to tell who was worse. The stock plunged 65% under Ullman (Act I), 54% under Johnson, 58% under Ullman (Act II) and 66% under Ellison.

So I was surprised that Ellison received the praise of many writers reporting his resignation. “He helped turn around J.C. Penney,” said The Street. In what universe that happened may never be known.

Not only do the writers let Ellison off the hook, they seem to rally under a common theme: it’s all Ron Johnson’s fault. After all, Ron was in and out in less than two years, and the stock was decimated during his reign.

However, this narrative ignores two major facts. First, JCP had already lost more than half its value before Johnson took the reins. Second, Ullman and Ellison succeeded only in driving JCP further into the ground.

The truth is, Johnson’s vision was correct and necessary. History has now proven that JCP was (and is) doomed without a radical plan for reinvention.

The company committed the classic sin of throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

The joy of hindsight

Years later, there’s no need to theorize about this stuff. We can clearly see what happened.

Fact #1 is that that JCP became a sinking ship in 2007. The recession started the decline, but shopping habits were changing drastically in the age of technology. JCP’s base of old customers was shrinking, and could no longer be counted on to generate profitability and growth.

Faced with this existential challenge, the JCP board went shopping for a CEO qualified to lead a large-scale transformation. Ron Johnson fit the bill perfectly. JCP’s stock rose 14% on his hiring alone.

What followed was a love-fest, which quickly morphed into a hate-fest. With the company’s stock reeling, Johnson was out—but the story didn’t end there.

Next came Ullman, followed by Ellison, and the decimation of the company’s value continued.

You can look at this two ways. Either Johnson’s leadership was so disastrous that no CEO on earth could ever help JCP recover—or the two subsequent CEOs simply didn’t have the vision.

Ullman and Ellison never even talked about reinvention, lest they be accused of suffering Johnson Syndrome. Instead they talked about finding new efficiencies, tweaking product offerings and shoring up finances.

Ellison specifically focused on getting existing customers to buy more—not on attracting a new generation of customers. There was no talk of rethinking JCP to the core.

Johnson, on the other hand, actually had a brilliant plan. Yes, it had a fatal flaw (we’ll get to that in a moment), but he created a detailed blueprint for reinventing the dying retailer. It was enthusiastically approved by the JCP board. Industry experts were so impressed, JCP gained a whopping 18% the day it was unveiled.

Johnson’s plan addressed all of the challenges.

JCP stores would be beautifully redesigned as a “mall within a mall.” Younger, more affluent shoppers would be attracted by desirable quality brands and expert assistance.

The new JCP would lure new customers to the store by offering a whole new shopping experience—something they couldn’t find online. Respect for the customer would reign supreme. Instead of falling back on the pricing trickery of never-ending sales and coupons, JCP would offer everyday low prices.

Cue the fatal flaw

As Johnson himself admits, he simply went too fast. He cut the coupons and sales before the stores could be physically transformed. In doing so, he alienated the old shoppers before he could attract the new ones.

This was a serious mistake in the execution—not in the plan itself. But in its state of panic, the JCP board felt compelled to jettison the plan along with its author.

Ullman and Ellison tried every trick in the book to return to the Time Before Ron. Unfortunately, it was an outdated book, and the efforts did not stop JCP’s decline.

Why anyone would lust for the pre-Johnson days is beyond perplexing, since the JCP of that time was already suffering a five-year decline. That would be like a ghost wishing it could go back to the death bed.

Good help is hard to find

At every point in JCP’s 11-year downward spiral, the company has needed a leader in the Johnson mold—a creative and strategic thinker with retail in his/her blood, a track record of reinvention and a true connection to modern shoppers.

Instead, they brought back Ullman, the CEO who had presided over the first five years of JCP’s slide. Then they brought in Ellison, whose track record (CEO of Lowe’s) didn’t demonstrate any understanding of lifestyle retail. Neither had any “reinvention” credentials.

Following the Johnson experience, it seems that the board’s guiding principle has been “better safe than sorry.” But being safe will never create sweeping change, and it’s making shareholders sorrier than ever.

Bold brains needed

I will forever believe in the power of smart. Reinvention is the greatest challenge in business, but smart people can overcome any obstacle—even existential ones.

So I’m sorry, but I can’t accept that Ullman and Ellison were doomed from the start. The power to reinvent JCP, to make an imaginative leap, to do something that’s never been done before, was always in their hands—they were simply the wrong men for the job. They were timid in a time that demanded bold.

Creating an amazing customer experience is a vastly better way to revive a dying company than firing up the coupon machines.

Ron Johnson was right—and the five years of wrong that followed him are pretty convincing proof.

100% agree!

Ron Johnson and Michael Francis developed a brilliant strategy- the implementation was just too much, too fast.

Great POV, Ken!

I remember reading about Ron’s hiring and had been looking for an epilogue to this neoJCP store, this was a great summation of the plans and missed opportunities, and ultimately the reversal of course that a company without vision tends to take into the abyss.

I agree with your take on Apple’s vanilla ad direction, why isn’t Spike Jonze doing more?

He had a great idea. The associates were happier not having to deal with all those dumb coupons and the customers were happy seeing the lower prices, but it was a hard sell to get them off the ingrained concept of those coupons. They were actually were paying less for their items without the coupons then with, but they felt as though they were missing a discount. If they would’ve thought about it the credit card rewards were their coupons based on how much they shopped. The company was saving a ton of money not having to pay for all those sale flyers, a team to change the ads for each sale (which in some cases were 3 and 4 times per week at holiday time). The associates didn’t have to worry about where to hang new items for fear it wouldn’t be signed properly and somebody would complain. It was a win, win, win for all, but noooo, they HAD to have those dreadful coupons!!!

As a person who worked and survived the Ron Johnson era, I can’t…or I can..tell you how wrong you are about a lot of this…of course JCPENNEY was on a decline, duh..all brick and mortar retail were on the same decline…bright spots here and there, but come on, man…really?…..that’s the work your showing to support your theory….what the Ackman/Johnson hamfisted shakeup blunderbus / clusterfuck of bad ideas, hubris, and tunnel vision did was bleed a once cash and asset rich company dry….it was all theoretical and as he said, done to fast…give me a break…his ideas would never have worked…he literally did the opposite of what everyone in the industry knows and repeats, as a mantra, “don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater”…at the same time, didn’t even bother to study and learn from Walmart’s mistake of throwing a bunch of money into an unnecessary NYC corporate presence…and giving money away hand over fist to the guy who designed the apple stores to apply his aesthetic and layout theory to Jcpenney….anyway…many levels of this, sorry to get in the weeds…Ron Johnson is a classic case of someone riding the waves of others successes ie target and apple…he was a shitty choice, I always wondered what Ackman’s reasoning or how much thought he put into it..or not..when you’re that rich, I guess you can make these kind of things happen to no consequence of your own

As a person who worked with Ron Johnson at Apple and JCP, I disagree with your disagreement. As I’ve said often (and Ron has said as well), he did move too fast. And you just said the same thing. But at least Ron was moving. As I point out in this article, JCP has been on the decline for years, and that’s because it being sucked into the same vortex as all the other brick-and-mortar stores. That the department store concept needs to be reinvented for a new generation isn’t up for debate anymore. For JCP, it’s either do something fresh and new, find a new way to appeal to younger and more affluent shoppers, or die a slow and painful death.

I don’t know what your role was at JCP, but I do know from my own work with Ron that there was great resistance to the change he wanted to make. I worked with some horribly short-sighted people at JCP who didn’t understand the degree of change that was needed. They clung to their old ways—convinced that if they could just do those things better, they’d be just fine.

By coincidence, I see in today’s headlines that right now JCP has no CEO and no CFO. It just keeps getting worse and worse for this company. I never claimed in my article that Ron Johnson’s way was the only way. My point was that of all the CEOs before and after him, Ron was the only one willing to take on the existential problem that is staring JCP in the face. Everyone who clings to the old ways (including the Board), will be out of a job when the company goes belly-up. For the sake of all the families whose lives depend on JCP’s profitability, I truly hope they can attract and empower a visionary leader capable of creating a JCP that appeals to today’s shoppers as much as it decades ago. Given the track record of JCP’s board, however, I think that the chances of that are slim.

Hi Ken,

Thank you for this interesting take – I’m doing a final project on JCPenney’s decision to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy for my corporate finance class, and I’m trying to learn as much as I can about the company and the circumstances that led to its downfall. Your opinion as an insider is very much appreciated, especially since it provides a perspective far different than the mainstream.

My question for you is this: what do you have to say about the additional $2.25 billion in long-term debt that JCPenney took on under Johnson? Under his tenure, the company’s long-term debt nearly doubled. Ullman is on record saying that this decision prevented the company from being able to take on new investments (i.e. the “revision”/pivot undertaken by Nordstrom), presumably due to a debt overhang problem.

To me, this paints Johnson in a bad light, and gives the subsequent CEOs an excuse as to why they didn’t pursue new, innovative investments. Also, I’d expect Johnson as a Chief Executive Officer to be able to “execute” his disruptive, visionary plan effectively — it’s difficult for me to give him a pass on moving too fast and alienating the JCPenney’s customer base, as you’ve admitted he did. Especially when we consider that he put the already-struggling company in such a precarious financial position with respect to long-term debt.

That being said, I do agree with you that the board probably overreacted and fired him out of fear — in hindsight, they probably should have stuck to their guns.

I would be very interested to hear your thoughts! Thanks.

I am that old 66 yr old customer who has shopped at JCP SINCE i was 8 yrs old thats a long time but ,i loved there clothes ,You could not have said it better in your responce ,it was brilliant ,Most shopping i do is of coarse ,JCP but on line i never go in the store or for that matter Malls ,Most everything i get is from Amazon there shipping is amazing never any mistakes ,I have NOTHING BUT PROBLEMS getting my order rite at JCP ONLINE i cant buy my favorite all Cotton Airazona chinos ,a they send the wrong model”low waist polyester crap,or tell me it was dropped off and i know it was not as my front porch is seen by my little companion that barks any time there is anyone near the door there online help sucks and 8.95 shipping cost is nuts ,i dont want to spend 100.00 Every time i shop GOOD BY JCP WE ONCE LOVED YOU BUT LIKE MY X WIFE WE WONT MISS YOU

I too, was there for the debacle. Johnson and his legion of sycophant morons not only had quickly-applied terrible ideas, but had zero respect for anyone who came before them — including every associate in every department at corporate headquarters. His numbskullery knew no bounds, and there wasn’t a trifle he wouldn’t get involved with. At one point he insisted he write the subject lines of all the marketing emails. He took the School Of Steve Jobs to insane levels, which only works if you are brutally talented. All he really learned from Jobs was the prideful cruelty that sometimes comes with insane talent. Johnson had no talent, which, by the way, was the only way anyone could have survived under Jobs! Steve Jobs needed soldiers, not thinkers, and Johnson was the best. When put into a role wherein he actually had to understand retail, he sank like a stone.

Your opinion was kind of fun to read, until the train wreck at the end where you display a serious lack of understanding about Steve Jobs’ leadership style.

Steve wasn’t looking for soldiers, he was looking for the best and brightest (at least at the upper levels). He repeatedly said that recruiting brilliant people was his most important job as CEO. Contrary to what some people (you) think, he did not micro-manage. Instead he tried to create an environment where smart people could actually do their best work. He recognized that he did not have certain talents, and relied on his hires to apply their expertise. His role was to provide the vision, and to make sure everyone was working toward that vision. I know because I was one of those people, and Steve made no attempts to control me. We could have loud debates and if you had a passionate point of view, it was entirely possible to convince Steve that your idea was the best idea.

But getting back to the JCP saga … read my reply to “M” above. Most of it applies to your comment as well. The point of my article wasn’t that Ron’s ideas were the only ones that could ever save JCP—it was that he was the only CEO during JCP’s slide downward who had creative ideas to re-invent the company for a new generation of shoppers. If you hate Ron, you have to hate the others in this parade of CEOs even more, because they succeeded in dragging the company lower and lower, to the point where many have given up hope. Now the CEO and even the CFO have abandoned ship.

Ken,

The point is Ron was so caught up in his idea that he didn’t take the time to test it and patiently work through the details and results. Kind of like Dr Frankenstein in his lab. He got caught up with his success at Apple and the word ‘Genuis’ and thought he could translate his sucess at cool high tech products to clothing/home retail. We were all excited at the possibilities when he first came on board, but he quickly mowed the wrong path to any possible success, and sent a lot of good, talented people packing, AND decided that a 100+ yr old company should operate like a start up. It was a combination of a lot a of bad impatient decisions. Saying the other CEO’s were worse then Ron is not even close to fair. They may not have had his mad scientist vision, but they attempted to take a much more reasonable path. In the end, the fall of JCP was inevitable because of the times we are in, Ron just strapped on the rocket boosters to get them there even quicker.

I’d just push back on two of your points.

Of the CEOs who followed Ron, you said that they didn’t have Ron’s mad scientist vision, but “they attempted to take a much more reasonable path.” With the company is spiraling downward, in an industry that was spiraling downward, the “reasonable path” is never going to work. JCP needed a bold vision, a reinvention, a resurrection, a rebirth, whatever you care to call it. A “reasonable path” is exactly what the post-Ron CEOs tried to do, as you say—but the result of that approach, over a period of many years now, speaks for itself.

You said “the fall of JCP was inevitable because of the times we’re in.” Well, it’s true that the fall of JCP could be foreseen because of the times we’re in. If it was inevitable, the JCP would have just packed it in. They recognized the existential threat, and they knew they had to change the course of the company. That’s why they hired Ron Johnson.

Remember, Ron didn’t act alone. His vision for a new JCP was unanimously and enthusiastically approved by the JCP board—made up of more than ten industry experts. It was also widely acclaimed by Wall Street retail analysts. The only flaw—and it was a doozie—is the “rocket booster” effect you noted. Ron moved way too fast.

I think Ron Johnson had some good ideas. He was completely undeterred from his mission of creating a perfect shopping experience that could be revamped a section of the store at a time at somewhat marginal cost. Vendors were reported in the news to be forming a line to sign up for his venture. Problem: He forgot to invite the customer to the party. The products he wanted to sell were boutique, niche brands with little to no profit brought to the bottom line. His actions cost millions instead of thousands and he wouldn’t listen to associates that had decades of experience with the JCPenney customer. Many of his ideas were ahead of their time, and most likely will be adopted in a future where the technology marries with cost of doing business. Ron bled the company dry and had the Board not acted, it would have failed long ago.

You raise an interesting point about the JCP debacle. You say that by removing Ron, the JCP board saved the company from going under. Well, not so fast on that one. The reality is that when the board sent Ron away, it was 18 months into a transformation it had approved with great fanfare, and understood to be a five-year mission.

At that point, they had two choices. They could continue with the transformation and make the necessary adjustments to the plan, or abandon ship and try to win back the customers who had been lost. They chose the latter. Unfortunately, the old customers were the reason JCP was failing in the first place. They were old-generation coupon hunters, fading in number, who simply couldn’t sustain JCP in the new world of retail.

The board knew that JCP’s long-term health rested on its ability to attract younger, more affluent customers. When Ron left, that understanding seems to have left as well. “Stopping the bleeding” is not a recipe for retail greatness. Unless JCP ever gets up the nerve to hire a truly visionary leader, one who is willing to take some risks, it’s hard to imagine the stores will be around much longer.

I was a vendor to JCPenney from 1990 to 2016. The downfall of the JCPenney retail chain is significantly more complex than portrayed here. Did the CEO’s hasten the downfall, of course, but the major cause was much more than just the CEO.

One of the first issues was forgetting the value of the JCPenney private brands which were seen, by consumers, to be national brands. The budget brand Towncraft was eliminated along with many great products that had been paying the bills for decades. The St. John’s Bay brand completely lost its way and became a hodge-pudge of not assortments but a list of “my favorite things” from various departments. New brands such as Mixit were invented but never really stood for anything in particular.

Anyone spending 4 hours a week in the stores would see two things very quickly: 1.) the Penney consumer was older and 2.) Young families were passing through from other mall stores without making a Penney purchase.

Ron Johnson was right about a few things, the most important was that new consumers were required if JCP was to survive. However, he did not have the foresight to consider testing new formats/assortments to attract a new consumer; nor, did he have the foresight to test alienating existing consumer by changing the entire pricing structure and eliminating coupons. Basically, wanting new consumers and actually attracting them are two very different things. Keeping the doors open by serving the consumer you have is critical to generating profitable income allowing time to make sure a new direction will succeed.

During the timeframe being discussed another important change took place. This change began to place the responsibility of an assortment’s success on the vendor who frequently had little input into the development/design of the product. Ultimately, this process caused a degradation of the product quality.

Finally, under the leadership of Ron Johnson, the input of experienced associates was ignored almost totally. In fact, hundreds of these associated were “RIFed” and replaced by inexperienced new people.

The CEO’s who rode the stock down bear the responsibility for the fall but it was a multi-faceted, complicated fall and not the least reason was losing the consumer who originally made JCPenney the retail giant it once was.

Yes, yes and yes. The mission was to attract younger, more affluent customers. JCP could never survive in the digital age without them. Ron moved too fast, and that was a mistake. The stores weren’t “new enough” yet to attract the new customers, and the changes (like eliminating coupons) drove away the old ones. Ron now admits that the changes should have been far more gradual, so he could bring the old customers along.

Many have criticized Ron for not doing any testing before making his changes. No argument there. Not to let him off the hook, you have to also remember that he didn’t make his moves in a vacuum. The board approved Ron’s vision and all of the major decisions he made to implement the vision. And the board was made up of more than ten retail industry experts. So if you wonder why on earth Ron never thought to do some focus groups, you also have to wonder why on earth the board so happily approved these things.

I agree that the fall of JCP is a complicated story, and there are many factors that came together to create the mess. I hear what you’re saying about Ron ignoring the input of experienced associates—but I also know that turning around a company like JCP is an unbelievably difficult task. It’s, as they say, like turning around an aircraft carrier. In a hundred-year old company, there will inevitably be a lot of people who disapprove of the new plan, or who actively work to undermine it. Not to be brutal, but to find a new path forward, that “old-school” thinking just has to go.

It is far more than coupons. JCP management team is stuck in the 1970 mode, where corporate people know what is best for everyone, and upper management know what is best for lower management. No one takes ownership, the store management are elfs toiling away at following corporate directives ( with no mindset to think what is best for their store or customers), the store associates do not have have any input into improving the customer experience (and if they do take a little initiative, they are quickly repremanded). JCP corporate management liked their little power world and did eveything they could to resist change and gave little help in implementation. It is said Johnson went too fast, his major flaw was not developing and training a team that was willing to “drain the JCP swamp” and embrace change and give constructive input in implementation. Silence on their part meant resist this change so “my little world will stay the same”. JCP management does not respect its associates, its customers or any changes that will force corporate management people to change. JCP needs change management training, top management personnel evaluation, and a big dose of total quality management training. Example: a visit from district or corporate management is a report card review of the implementation of corporate directives, rather than establishing an environment for improvements at the store level. The district or corporate manager never has said “how can i help you do your job better”, instead they point out what still needs to be done to impliment the corporate directives. One other point fro experience, corporate does not beleive thier ideas should be challenged or test run (mainly a test run would set the stage for their ideas to be challenged). JCP needs to keep the main thing, the main thing and that is providing the best customer experience possible that results in profits for the company.

Vision is only the seed, an idea. Without a solid plan for implementation all visions will fail. Ron Johnson may have had a vision but he failed as a manager in developing an implementation plan and training a team to implement the plan. That was Johnson’s short coming. His ego got in the way of good management and implementation strategy.

Just a couple of observations from a shopper.

1. JCPenney stores are ugly. Even the newest off the mall stores are offensively bland. Think about those last two words. It’s not easy to be offensive and bland at the same time, but that’s exactly what those stores look like.

2. All the low-margin hardlines departments that department stores got rid of over the years, are the ones that drove traffic. Whereas discount stores during the Golden Age of that industry used to carry crappy items, now the stuff you buy at a discount store are fairly high quality. Should JCPenney be looking at a Kohl’s format, but with a lot of staple items that draw people to the store?

A good example is the kind of mix you see in a Menards store. It’s mostly a home improvement store, but it also has a little bit of clothing, some toys, some automotive, a small grocery section, etc.

3. I’m middle-aged, and not too keen on spending $80 for something that has a Polo label on it. St John Bay was perfectly acceptable to me. The styles were reasonable, and the quality was decent. Stupid move getting rid of that line.

4. A lot of people compare JCPenney to Kohls. To me it boils down to one thing. To me when I think of Kohl’s, I think of the word polyester. JCPenney to me means affordable clothing and cotton.

5. EDLP is great when you are Walmart and the prices are genuinely a good deal, although it’s hard to tell anymore because everybody’s prices seem to be roughly the same except for Kmart which is 20% higher. I put JCPenney’s attempt at doing everyday low prices in the Kmart category.

6. Kroger has developed a pretty good line of private label brands. I remember when I was a kid and my mom would bring home canned vegetables with the Kroger label on them. Having to eat those items for dinner was like a death sentence. These days, Kroger brand stuff is pretty good. I think JC Penney had some of the same thing going on with their in-house brands. Like I said above, I thought St John’s Bay was pretty good overall. In my opinion, they should stick with smart looking items, cotton with more of a classic look.

Speaking of Kroger, isn’t it interesting how the average Kroger store or Walmart, is a lot better looking than the average JCPenney for Macy’s store? Maybe what they need to consider doing is cheap updates to their stores, but on a regular 5 year rotation, instead of putting a lot of money into stores and then not touching them for another 40 years.

I don’t pretend to be an expert, just a random customer who would like to see JCPenney survive.

Hey Nick,

Thanks for the thoughtful comments. I think you have to keep in mind that JCP’s biggest problem, even before Ron Johnson gave it a try, was that they needed to attract younger, more affluent customers. The old customers (buying the old brands) were becoming less and less profitable. JCP had to reinvent itself or die. And you’re right, JCP’s stores were just butt-ugly and didn’t exactly scream “quality.” Yes, Ron did improve the stores interiors to a degree, but there was a far bigger plan than what you saw. I think I discussed this in more detail in my book Think Simple (memory fades!), but Ron created a prototype store in Dallas to experiment with different ideas. I’ve never been a JCP shopper myself, because the brand always felt low-quality to me—but when I walked into the prototype store I was blown away. There were gorgeous displays, wide aisles, higher quality brands, a large collection of “stores within a store” that were to be manned by brand experts, counters where one could get free advice, and much more. I would have LOVED to shop in such a store. That was all on the “to do” list, and for the whole chain of JCP stores, it would have represented a mega-investment. Personally, I think it’s a real shame that none of this ever came to be. I too would have loved to see JCP not only survive, but light the way for a whole new kind of department store. Absolutely, there were mistakes made, but I do believe the JCP board threw out the baby with the bathwater.

No question these all sound like great ideas and I get that they were nowhere near being fully implemented, provided you are careful about your price points. I’m going to trust that a guy who cut his teeth at Target is going to appreciate this. I think the name of the game is providing value. It seems to me that Costco is another good model from the standpoint of attracting a more upscale shopper because it provides value. Not the prettiest stores, but people seem to like what they offer.

Don’t get my comments wrong, I know the JCP brands weren’t exactly the Kirkland of softlines. But like I said, I’m middle aged and don’t care about paying out the nose for a name brand anymore. (I would do it for dress clothing, but who wears dress clothing anymore?) Maybe part of my impressions have to do with age, but not only are the stores ugly these days, most of the fashions are, too. I think there is money to be made on selling affordable, tasteful, merchandise with a little fashion-forward stuff thrown in. Or maybe I’m just getting old …

I totally agree with your comment i once bought Ralph Lauren Polo only but ,at 66 yrs old who the hell gets over dressed these days and my last years on the road ,as Sales Mgr and salesman for a major Office equipt. Company as i would drive to all my sales calls i started wearing my NOW JCP Airazona chinos and cotton only oxfords or Polos so JCP is a sunken ship and is to bad

P.S. I do give Ron Johnson credit for improving the look of JCPenney stores. I don’t think they appreciate how much this was desperately needed.

The first time I had heard of the “Store of stores” concept , it was with Ron Johnson, most retailers do it. Hell, even Best Buy does it.

Getting Ellen Degeneres to promote a Department store which had a conservative Christian customer based in the midwest – that was a disaster.

Ron Johnson had some great ideas, but some were very stupid. The way the stores had transformed was just amazing, but he failed to understand his customers