The war without end: Mac vs. PC

Yikes! Intel has launched a new anti-Mac campaign. The nerve of those people—they signed Apple’s “I’m a Mac” guy to attack his former employer. This is war!

Actually, it’s only the latest battle in the Mac vs. PC war that’s raged for 38 years. It’s a war being waged on three fronts—technology, marketing and culture.

And guess what. Through all these years, Apple has almost always been the aggressor. Only rarely has the PC side felt threatened enough to push back.

So, what do we make of Intel’s new campaign? Hold that thought, because it’s best judged in the context of history—and a juicy history it is.

I might overlook some important moments, but I’ll give it my best shot.

Apple’s “gracious” welcome

In 1977, long before Macintosh, the Apple II became the first successful consumer computer.

In advertising, Apple described it as a “personal computer”—a moniker later appropriated by the PC industry.

Apple was a classic American success story. Two young guys with an idea, starting a company in their garage, grossing $118 million annually by 1980.

Cue the big scary monolith. IBM saw a new business opportunity and in 1981 launched the IBM Personal Computer.

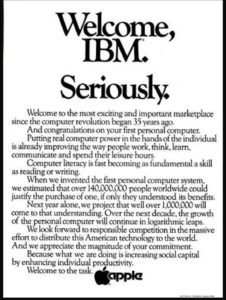

What could Apple do? They ran this ad. Basically, it was David welcoming Goliath to a market in its earliest days, taking some credit for being the first guys there.

As you might have deduced, Goliath wasn’t intimidated.

Macintosh fires the first shot

Up until 1984, computers from both Apple and IBM weren’t too far apart philosophically. Both worked with a command-line interface. Both came with a learning curve.

Macintosh changed that. It was the biggest think different moment in Apple history, 13 years before the advertising theme line. The graphical interface was a revolutionary, intuitive, more human way to work on a computer.

The famous 1984 commercial that launched Macintosh, directed by Ridley Scott, almost never ran. (Good story here.) But Steve Jobs was determined to unveil the new computer with a cinematic attack on IBM.

Obstacles overcome, the ad ran during the 1984 Super Bowl. Without naming IBM, and without ever showing a Macintosh, Apple portrayed IBM as Big Brother and Macintosh as the liberating ray of hope.

Did Apple’s attack work? In terms of sales, not so much. But it clearly imbued Macintosh with the feisty, underdog, maverick personality that would drive its advertising for decades to come.

It was also Ground Zero for the culture war, portraying the two platforms as worlds apart in human values.

Let us all join hands

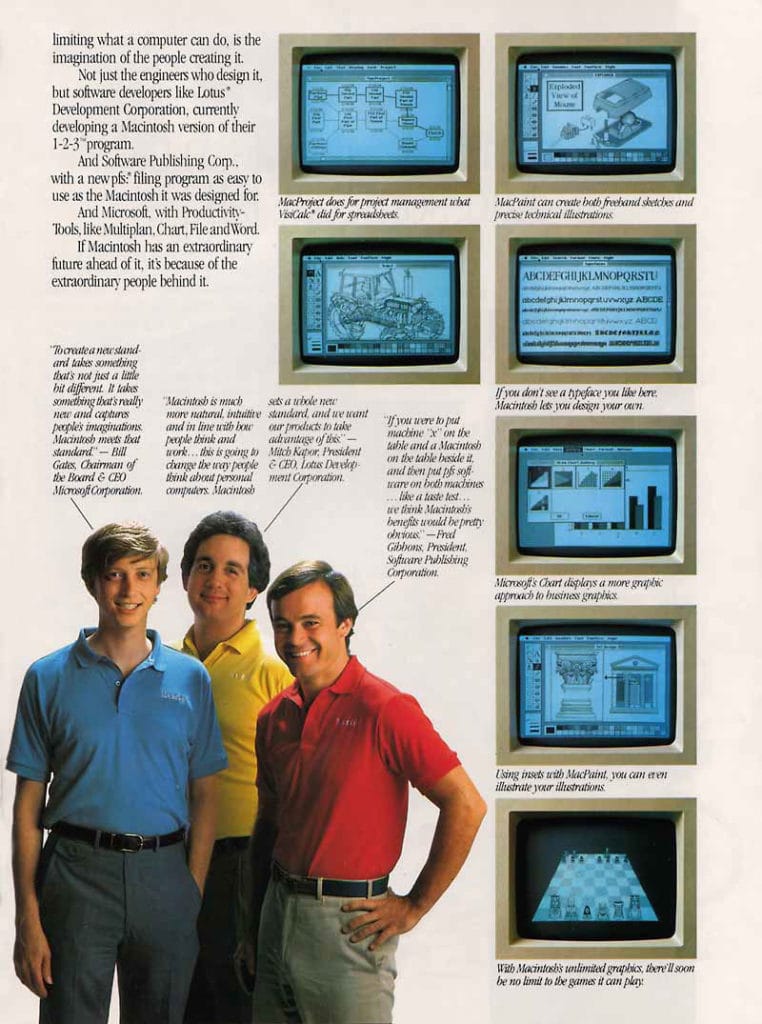

Before Macintosh launched, Steve Jobs made sure it had friends in high places.

How many even remember that Steve recruited some software guy named Bill Gates to help make Macintosh a success?

Bill was one of the developers featured in the multipage insert that introduced Apple’s new baby.

It gets better. In a Macintosh promotional video, Gates boldly says, “We’re planning that over half of our retail sales next year will come from Macintosh software.”

In these early days, Microsoft was getting rich supplying PC DOS to IBM PCs, and Bill saw Macintosh as an opportunity to expand his market.

Who knew what nasty turns this love-fest would take before Steve and Bill would ultimately call a truce, and Microsoft would chip in to help keep Apple alive.

Macintosh pokes the bear

Never mind that Bill Gates gleefully joined the Macintosh launch club. After the 1984 ad ran, Steve Jobs ditched the symbolism and went right for IBM’s jugular.

In later years, Steve would express the belief that having an enemy is a terrific way to focus the company’s resources, create great ads and attract more attention. This was exactly his approach in the first extended Macintosh TV campaign.

In the Manuals commercial above, Apple offered a simple side-by-side comparison, mocking PCs for their complexity. It got way nastier when the agency moved on with the Test Drive A Macintosh campaign. This series featured people getting so frustrated with their PCs, they literally destroyed them—one with a chainsaw and another with a shotgun. Try to get that through network clearances today.

Did Apple’s attacks work? Let’s just say Goliath marched ahead, undaunted.

Microsoft “invents” Windows

Bill Gates truly did see something big in Macintosh. So much so that Windows 2.0, unveiled in 1987, showed striking similarities. Enough for Steve Jobs to file a copyright infringement lawsuit.

It was interesting to watch corporate PC gatekeepers, who previously ridiculed the graphical interface, fall in love with it.

Microsoft behaved like a leader in its ads, never mentioning Macintosh and claiming the graphical interface as its own. The defenders of the PC realm already had plenty of reasons to reject Macintosh—network and software compatibility, security, etc. Now they had the benefit of the graphical interface as well.

Apple did its best to knock down the objections one by one, but culturally it was a bridge too far. In a world dominated by PCs, few were willing to risk their jobs by bringing in the rebel technology.

Apple goes myth-busting

When John Sculley ousted Steve Jobs to become CEO, he replaced Jobs’ ad agency Chiat/Day with BBDO, the agency he used as CEO of Pepsi.

The first campaign from BBDO was The power to be your best. Only one of these commercials mentioned IBM by name, but nearly every spot was designed to tear down the myths that led people to choose IBM or the growing number of PC brands.

One was particularly interesting. It showed a salesman failing in his effort to sell a tough corporate exec on a new computer system. The ad led the viewer to believe that the exec is thoroughly bonded with IBM, but there’s a twist at the end. The salesman is actually from IBM and the exec is the Macintosh guy, unwilling to change. Bang!

In print, one ad played off the belief that “nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” The headline was written as if it was breaking news: “MIS Manager buys Macintosh, keeps job.”

Did this campaign work? The TV component, directed by heavyweight Joe Pytka, won a ton of advertising awards, so that’s something. But when the smoke cleared, Macintosh was still the underdog.

It’s common sense, people!

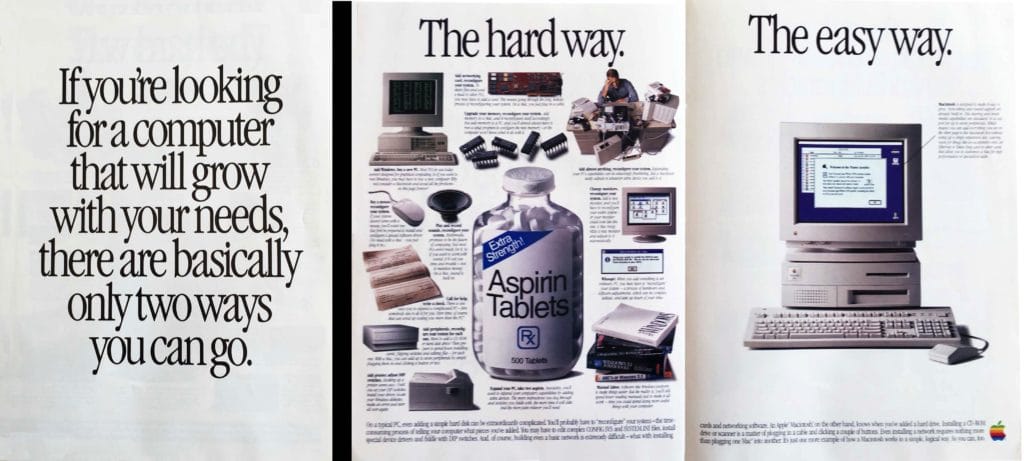

If all the digs couldn’t turn the tide for Macintosh, maybe pure logic will would? That was the thinking behind Apple’s next attack on PCs—The hard way vs. the easy way.

These ads took up an awful lot of space, spanning three full newspaper pages. In images and words, the left-right comparison made it clear that Macintosh cuts through complexity to help you do things faster and better.

Which sounds better? Hard way or easy way. C’mon, use your head!

Unfortunately, most people’s heads weren’t wired this way. This campaign did not juice Macintosh sales dramatically, but it did make Macintosh users feel good about their choice.

In your face, Windows

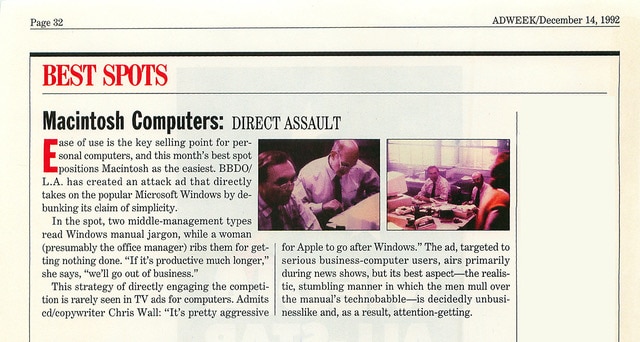

Adweek called it a “direct assault” on Microsoft Windows. Honestly, I barely remember this campaign, and can’t find any trace of it online. I found only this article, buried deep inside my own archives.

Given the creative director credit to the great Chris Wall, this would have happened during or immediately after The power to be your best.

It seems that Apple was fed up with Microsoft claiming that Windows was easy to use when Macintosh was clearly the King of Easy.

Hard to say if this campaign had any effect. I take the lack of an internet trail as circumstantial evidence that it was not a world-changer for Macintosh.

The Anti-Intel Trilogy

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the Think different campaign was born—but it would be eight months before Apple would have a truly new product to sell. What to advertise in the meantime?

These were pre-Intel days for Macintosh, which was still running on PowerPC chips. In Apple benchmark tests, a brand-new PowerPC processor was found to be faster than the fastest Intel chip in the newest PCs.

And so Steve found a new enemy to focus on. Even better, by attacking Intel, Apple would be attacking the entire PC industry.

This assault took the form of three ads. In addition to Snail, above, there was also Toasted and Steamroller.

Did this salvo work? It did. Macintosh fought its way into a conversation where it had been mostly forgotten—high performance. Now at least there was a debate. Progress!

Steve Jobs hoped Intel would sue, but it never took the bait, doing nothing more than rebutting Apple’s claims on the Intel website.

iMac joins the fray

When iMac launched in 1998, it picked up where Macintosh left off, positioned as the antidote to PC complexity. The ad above, voiced by Jeff Goldblum, literally refers to iMac as the Un-PC.

In another spot, Goldblum mocked PCs for being beige. One of my favorites made a damning attack on the PC world with nothing more than sound effects.

How did it work this time around? Incredibly well. iMac made Apple profitable again after many years of losses. It quickly became Apple’s all-time best-selling computer, and went on to become the best-selling single computer model of all time, from any company.

iMac was literally the starting point for Apple’s miraculous rise from the ashes.

Historical note: at this point, Steve decided to retire the word Macintosh. From this point forward, every Apple computer would be spoken of as a Mac. Simpler!

Refugees welcome here

Apple never gave up trying to shake PC users from their habit, but it did change tactics multiple times. The Switch campaign got a lot of attention in its day.

The campaign was a series of 30-second testimonials featuring real people—”Switchers”—who had crossed sides to become happy Mac users.

The above ad featuring Ellen Fleiss was controversial, as her style of speaking led many to wonder what she had ingested before filming her spot.

The campaign accomplished its goal, creating buzz with its quirky authenticity, Apple style. A human being talking to camera on a white background.

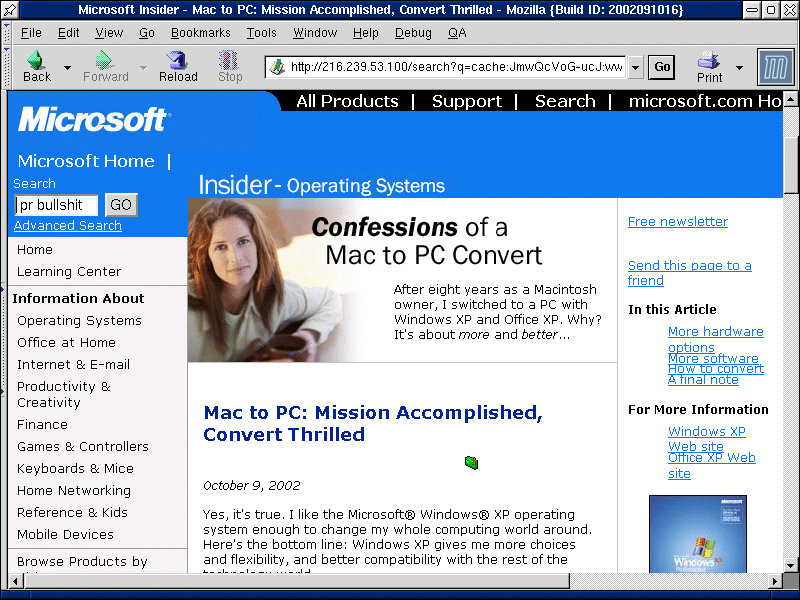

Microsoft finds its own Switcher

In days of old, Microsoft was particularly awful in its advertising. In this case, it developed a strategy that wasn’t inherently terrible—it was just executed in the clumsiest possible way.

After Apple’s Switch campaign picked up steam, Microsoft couldn’t resist the urge to beat Apple at its own game. On its home page, it featured its very own Switcher. This woman was a freelancer who told the tale that she’d used a Mac for eight years before finding PC happiness.

It was a lovely story. And completely untrue. It was soon revealed that the woman in the image was a model and the writer was actually an employee of one of Microsoft’s PR agencies.

Really? With millions of happy customers, mighty Microsoft couldn’t find a single legitimate Mac-to-PC switcher to celebrate?

Microsoft “regretted” the posting and took it down. But wow, what a display of incompetence.

Battle of the stereotypes

I’ve always felt that the Get A Mac campaign was advertising perfection—wildly creative and off-the-charts effective. To this day, it remains Apple’s greatest victory against the PC enemy.

Born at a time when Mac sales were fading, Get A Mac consisted of 66 ads over a four-year period beginning in 2006. If memory serves me correctly, Mac market share increased from about 4% to 10% during this time. Pretty extraordinary.

The concept was crazy-simple: turn Mac and PC into people, and let them have a friendly competition.

Enter the stereotypes! Mac (Justin Long) was casually cool, creative and productive, while PC (John Hodgman) was a vanilla officer worker, blissfully unaware of his shortcomings.

The campaign was a viral blockbuster. As it cut into PC market share, it also ratcheted up the culture war. Since the humor came at the expense of the PC character, many PC loyalists saw the campaign as mean-spirited or annoying—which only gave it more media attention.

Apple’s previous attacks were based on confrontation and/or logic. It turned out that humor was the most effective weapon. No chainsaws required.

Microsoft fights back with a mighty “Oh yeah?”

Tired of being Apple’s punching bag in Get A Mac ads, Microsoft offered its rebuttal.

The idea was to show that PC people are absolutely not the bland PC character depicted by Apple. They’re real people, representing many lifestyles and professions, doing great things thanks to Microsoft.

The ads featured a montage of diverse people simply saying, “I’m a PC.”

The mere existence of this campaign indicated that Microsoft was feeling the heat from Apple’s creative attacks. Microsoft was playing defense here—never a good look for a market leader.

This campaign was a feel-good message for the PC crowd. It came and went with little fanfare.

Intel buys the ultimate Switcher

When the Get A Mac campaign appeared, Macs and PCs were both running on Intel chips. Intel was delighted no matter which side you chose.

Not as much delight in Intel’s heart these days. Apple is dumping Intel processors in favor of home-grown silicon. The first M1 Macs are outperforming Intel’s PC offerings and getting rave reviews.

Two things reveal that Intel is suffering a bit of angst. One is the warning that CEO Pat Gelsinger gave to a recent all-hands Intel meeting. The other is the new Justin Gets Real campaign.

Over all these decades, this is the first time Intel has attacked Apple directly. And a global power like Intel doesn’t target another company unless it senses a disturbance in The Force.

Surely Intel sees the Justin Gets Real campaign as a major coup, turning Apple’s “I’m A Mac” guy into its very own Switcher. (And surely money had nothing to do with Justin’s change of allegiance.)

I must admit, I never saw this campaign coming. Certain things are carved in stone, and Justin Long as Mac Guy is one of them. So Intel does deserve credit for the big surprise.

But—watching the ads brings many other thoughts to mind. Here are the reactions I had after my first and only viewing.

Typically Intel. Having survived (barely) a tour of duty as Intel’s agency creative director, I know the company’s culture well. Hovering over every marketing initiative was the unwritten commandment, “test, test, test, and then test some more.” Too many great ideas were watered down or killed in the search for messaging perfection. In Justin Gets Real, I see nothing to indicate Intel has changed one bit.

Echoes of Sprint. Sprint signed Verizon’s Can You Hear Me Now? guy to be their spokesman a whole five years after the Verizon campaign ended. That’s already a lifetime in advertising years. Intel signed Justin Long 12 years after he last appeared as “I’m a Mac.”

How customers see Justin. This is like politics, where left and right see what they want to see. Among those who remember Justin as the Mac Guy, PC users see delicious irony, while Mac users see an actor selling his soul. Those who don’t remember him see only a mildly amusing spokesman making the big sell.

Who’s the intended audience? With Apple abandoning Intel, Job #1 is keeping PC users in the fold. Mac users are among the world’s most loyal, unlikely to follow the Pied Piper to the dark side. Unless delusion runs deep, this isn’t news to Intel. This is a PC user campaign, and any Mac conversions are just a nice bonus.

Slightly off-topic. Speaking of traitors, I’m reminded of the comedian Sinbad, who was a regular at Macworld events for years and years. In the early 2000s, I went to the CES show in Vegas, only to find Sinbad on stage singing the praises of Intel with then-CEO Craig Barrett. What’s with these people?

The writer’s dilemma. If you believe Justin is doing it for the money, you’re suspicious before he even opens his mouth. How do you begin writing a script for him? In Intel-world, the answer is to have Justin gush over PC devices with fake surprise (“Wow!”) and endless gushing (“Oh, that is so cool!”) The ads sound like they were written by the Intel marketing group—which probably isn’t far from the truth.

Ads as entertainment. Get A Mac scored points in the war by saying provocative things in the most entertaining ways. The combination of great writing and great acting made the ads so very buzz-worthy. Going out on a limb here, but I don’t imagine you rushed to share these ads with your circle of friends. They show traces of humor, but barely register on the Entertainment Meter.

Bombshell or unexploded ordnance? Even the greatest advertising idea in the world falls flat if execution is poor. In a parallel dimension, using Justin might have led to the bombshell Intel imagines this to be. In our current reality, it’s just another sales pitch.

The Fiction Factor. Anyone in Hollywood will tell you that real people are not nearly as compelling as fictional ones. Justin as Mac Guy is infinitely more interesting and compelling than Real Justin.

His secret past. Justin Long is more attached to the Apple world than you might think. Did you realize that he actually played Steve Jobs in the mediocre 2013 comedy film iSteve?

The Justin Brand. It’s no longer unusual for actors to dabble in commercials for a little extra cash. Sometimes a lot of extra cash. That said, the companies they choose and the quality of the scripts have a real effect on the actor’s brand. I worry for you, Justin.

Where does it end?

Spoiler alert: it doesn’t. It’s Apple vs. the mutually dependent Microsoft and Intel, now and forever.

But that’s a good thing, because it’s amazing entertainment for marketing enthusiasts like us. We’re watching gladiators in the Colosseum, minus the mess that comes with spears and assorted spikey things.

So thank you Intel for serving up Justin Gets Real. Opinions vary, but one day we’ll be able to say with certainty if this was a moment of brilliance or a mere blip in tech marketing history.

My money is on the blip.

That was a wonderful long history of Mac vs PC. Thanks.

Can’t forget this. The difference is, it’s clever. https://youtu.be/Bf5qZrFfQFg

Interesting, entertaining and good-natured walk down memory lane.

Thank you 🙂

Intel’s new ads reek of desperation. It’s quite sad.

Thanks ken for the great VS story.

Well put

Awesome, thanks!

I definitely agree that not much is changed at Intel. I do wonder if there’s some marketing guy at Intel that’s been there for 30 years that created this out of a grudge and a chip (pun intended) on his shoulder that he’s been carrying ever since the apple campaigns with Long. I wonder if it’s just more personal for one of these guys to take a jab at Steve Jobs posthumously to feel like they finally beat him at some thing.

Good theory, but I don’t think there was a marketing kingpin at Intel who had a grudge. The marketing group turns over fairly often. All the people I worked with were gone within a year or two after I moved on. Of course things could be different inside Intel marketing today (doubtful but possible), but I think the problem there is deeply embedded in the culture. It’s all about processes, testing and analysis. A powerful culture rewards those who conform to it and expels those who do not—and we all see the result.

Thanks for this, Ken. Really fascinating to hear your perspective on all this.

Making a person other than steve the face of the company was a wrong decision on apple’s part.

Dont you think so Sir ?